HANNAH VANDERMOLEN

By Virginia Rand

Photos by Ward Robinson

Originally from Boston, Hannah Vandermolen has lived between Los Angeles and New York City for the last few years, while achieving considerable success as a fashion model. She has also worked in music, both as a writer and a singer. Her main focus and passion, though, is her painting. She studied at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, Scuola Lorenzo de’ Medici in Florence, Scuola di Grafica in Venice, and the Gage Academy in Seattle before finishing her BFA at Cal State Long Beach. She attributes her creative endeavors to her artistic parents. Her father was her first teacher, and fostered her early interest in drawing.

I met Hannah when we appeared in a music video together for The Pixies, directed by The Pixies’ bassist Paz Lenchantin. Paz had asked me to pick Hannah up on my way to the shoot, because Hannah's taxi driver had decided he didn’t want to drive to Venice, and had left her on the side of Sunset Boulevard. I pulled over when I saw a sprite dressed in black. Elegant features climbed into the Bronco passenger seat, small boned fingers and big green eyes, her voice low and soft.

Today she is sitting before a shadow-laden easel streaked with the rich, dark colors of her oil paints. She is prepping canvases in spectral base tones. In a corner room of her Laurel Canyon home, her various paintings peer out from the slate blue wall, gazing with human features upon the masked mannequins and shelves of oddities that share her studio space. Hung up next to the south window is a copy of the poster she recently designed for the current A Perfect Circle tour. She paints while sitting on an embroidered pillow, cushioning the top of an old Nine Inch Nails drum throne. Turpentine lingers in the air.

ANIMALS: What was the last thing that you painted?

HANNAH: I started a new painting a couple nights ago. The last thing I finished was maybe two days ago, another self-portrait…because I'm so in love with myself. Just kidding, I'm tired of self-portraits. I’ve been feeling lethargic, not really wanting to paint, more interested in writing, and music. I feel like if one creative flow is blocked I'll try to jump in on another so I can still maintain a routine of making something daily.

My dad taught me when I was three, and was my teacher for most of my upbringing years. He always said it's important to keep exploring, don't get stuck in a routine, you can never fully master something.

Your work focuses on human form, though not necessarily a traditional depiction of human form.

That's kind of a riot against my maker. I always studied with representation painters. In the last years of my education there were two factions of painting professors, the abstract and the figurative. They hated each other, and really tried to manipulate students into choosing one over the other. They discouraged us from experimenting with both sides. I chose figurative, and opened my head up like a vessel, and received a strict, traditional knowledge based on renaissance painters, anatomy, structure, and form. I think what I do now is a bit of a revolt against all that.

I didn't really have the chance to study with any abstract teachers, but if you look at the best abstract painters, they were rooted deeply in figurative painting first. They were groundbreaking because they were taking away from what they had learned. It was so drilled into me, "This is the way, this is the routine, this is how you have to learn." How do you take that apart? At the end of the day, it's an individual thing. There's maybe no way to teach that.

Do people interpret your paintings in ways you didn’t intend?

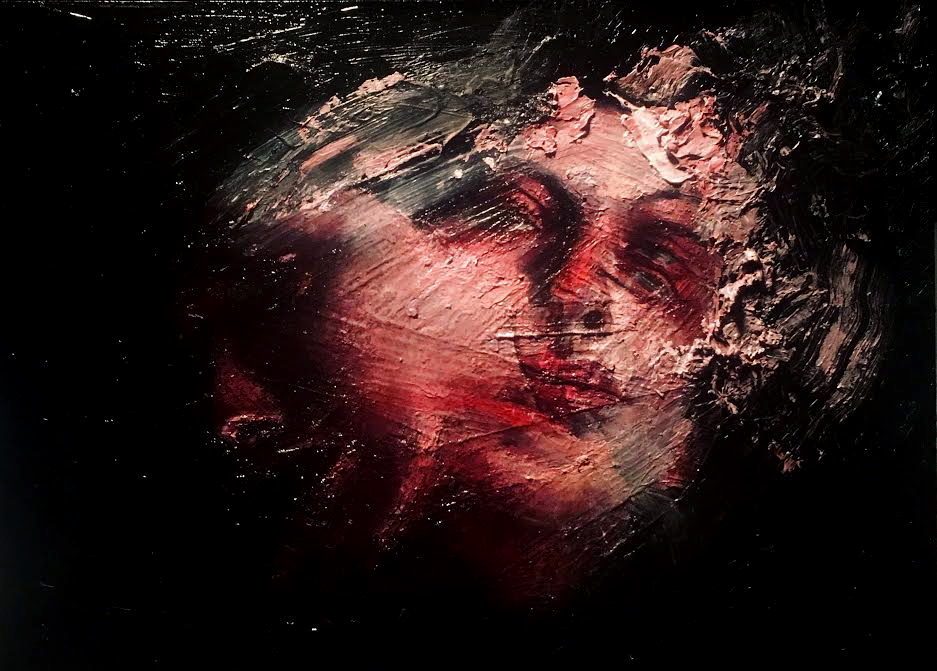

Lately, yeah. When I first started to experiment with abstraction, the colors I was using were a lot more inviting to look at. I was doing portraits underwater, how the water distorts the figure. It was the same idea as what I am doing now, but it was done in a more inviting, Monet-type way.

When I started experimenting with the muted pallets, the darker images that I've been making lately, a lot of people asked me if I was okay. I'm actually so much happier than I was then, and I think it’s because I'm expressing what I didn't want people to see that I had in me. But we all fucking do. We can talk about it, it's not scary if you put it out there and you address it. These are tools you can use to start to figure out how to live your life, what you want to do with it, how you want to be to other people. The distorted portraits are dark, but they're not meant to be frightening. I'm not trying to say anything like that, I’m just looking at a human being through a lens.

You have a history of doing anatomically precise drawings and paintings, and I understand you used cadavers as life models.

Yeah, I was so lucky. In the college that I graduated from, we had a cadaver lab for the biology students. In my anatomy class, we could study from the cadavers. We could touch them, maneuver the limbs, look at the different muscle groups. It was really fascinating. I was so obsessed with learning about anatomy at that point.

I was sketching a lot outside in my break periods. I was using oceanographer's pen and ink, and I was sketching trees. I was obsessed with the bark. When I saw those cadavers, I thought, “It's so much like those tree limbs. The way the bark grows is like certain muscle groups.” I was obsessed with limbs and hands and how they looked like tree branches to me. I would go in every day for a few hours and draw and paint from the cadavers. The biology class would be going on through the glass door. I could see them because the teacher would have to look in on me and make sure I wasn't doing anything suspicious. They thought I was super creepy. I had to get a special pass to go in every day and draw from the bodies. They kept saying "Why are you so interested in this?" I'd go "It's fascinating! Why are you not interested in this?" And they lent me bones, I could sign out bones and draw them at home.

Like a library book?

Yeah! But with human bones! My roommate was not so happy about it.

Does your work in modeling influence your painting?

It definitely influences how I work with models when they're posing for me. I know how it feels to be looked at. I know how exciting it can be, and how uncomfortable it can be. The last thing I'd ever want to do is make someone feel the way I have felt in some situations, which is also part of why I often do self-portraits. It's just hard for me to worry about making anyone uncomfortable, or feel judged. I absolutely don't want that. Also, because of the nature of the images, because they look so dark, I wouldn't want someone to feel like they were poorly represented. To me, the subject doesn't matter so much as the handling of the paint.

Do you formulate an idea and then get it down on canvas, or does it start to reveal itself as you go?

I think it used to be, ‘formulate an idea, get it down on canvas.' Now it reveals itself to me as I'm working. I'll turn the canvas upside down, around, I'll try different things. I'll put it away for six months, and then look at it again. I have to feel ready for it.

It's like an energy, if I push against it, I'm not going to get the result I want. Right now I'm just experimenting. I want to be more free. I want to be experimental and I don't want to be precious about everything, I don't want to feel attached. So sometimes I'll just let go, and literally destroy something. And then recreate it later.

What sort of things have you destroyed?

Portraits I didn't like.

How do you destroy them?

I've lit them on fire, painted them black, covered them in different types of metallic, experimented with different chemicals on metal to see what happens. I like to let the power get taken out of my hands sometimes. I like to relinquish control. Sometimes that means undoing something that I had started to over develop.

That is a core concept to some eastern thought, that there's a balance of creation and destruction.

And another thing is stopping before you go too far. That to me has been the hardest thing to learn in painting. Apart from everything else I think that's the hardest thing, learning when something's finished, allowing it to be finished.