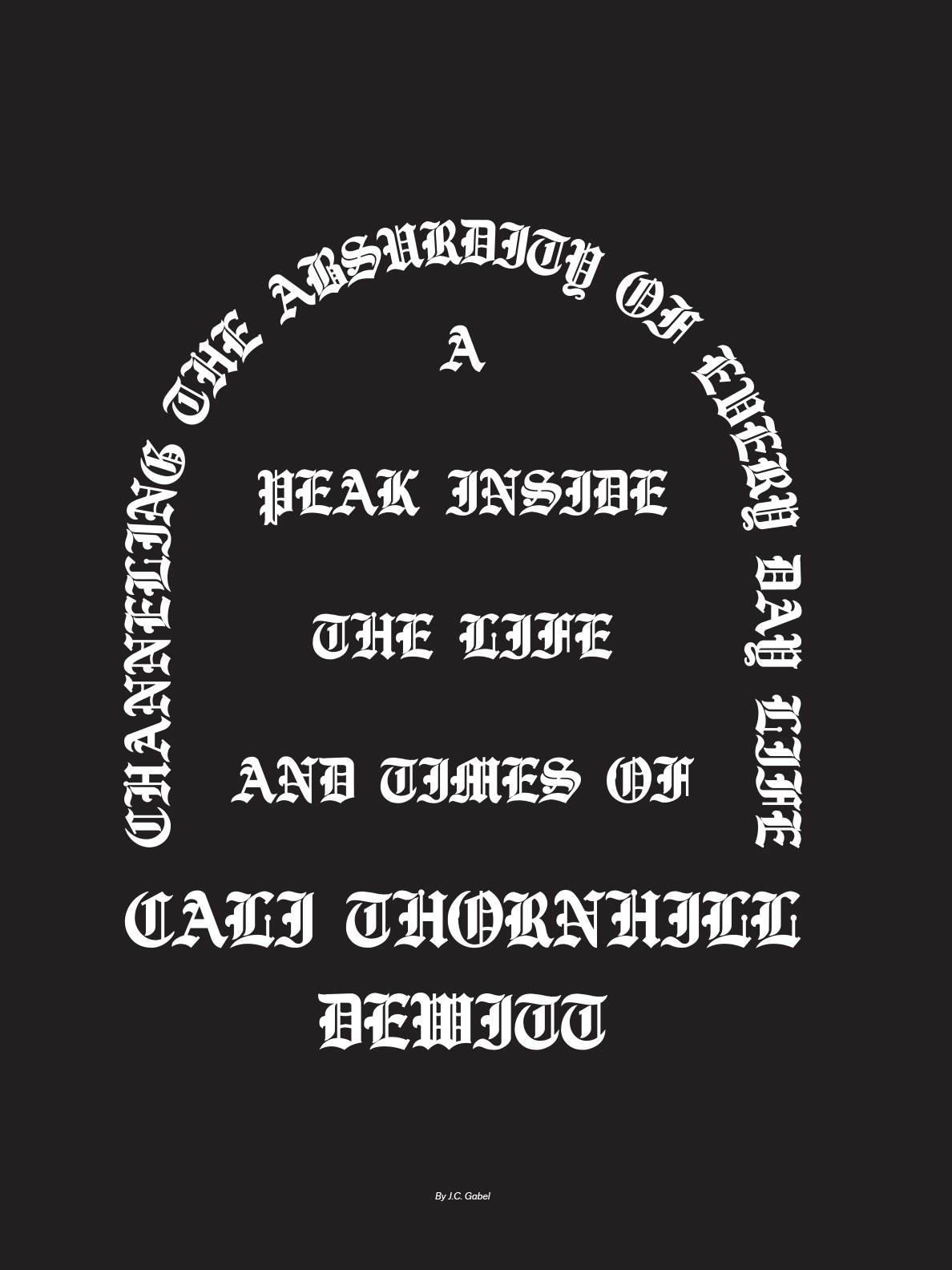

CALI DEWITT

By JC Gabel

Photos by Ward Robinson

Over the years, Cali Thornhill DeWitt, (born in Sidney, British Columbia on Vancouver Island and moved to LA at age 3) has engaged in a number of different disciplines, including a short-lived gig as a record A&R rep, photographer, blogger, record label honcho, music video director, and most recently fine artist.

It’s difficult to even remember in what context I first heard his name mentioned in conversation.

His Wikipedia page, not surprisingly, is flagged with one of those exclamatory warnings, telling readers “please help improve” the entry. Whenever it’s time to fact check a career biography that stretches more than 25 years and covers so much ground culturally - it’s never easy, regardless of the source. Such is the case with Cali.

Nevertheless, after speaking with several his friends—and then Cali himself—I could get a working time line down.

Cali had grown up in the San Fernando Valley north of Los Angeles, but left town at 19 to tour with the band Hole (this was in the early Nineties) and ended up in New York City for a while, then Seattle.

I think I first heard about Cali because he was—in his youth—the last “manny” to Kurt Cobain and Courtney Love, just before—and during—the time of Kurt’s death, in 1994. This was the music story tragedy of our generation, and 20 years on still hangs like a cloud over that mid-Nineties, pre-Internet period.

It is an unwanted distinction that Cali has spent the better part of his adult life putting behind him.

Since getting sober in 2001 Cali has worked on a steady stream of fruitful projects, first with Teenage Teardrops, the label he co-founded with Bryan Rae Turcotte, from Beta Patrol. He is obsessive about his photo blog WitchHat.biz, which his wife Jenna co-edits with him. Since getting married to Jenna Thornhill in 2010, by the way, Cali has taken his wife’s surname as the first of his two last names. The duo also collaborates on a myriad of projects, (zines and otherwise) under the moniker Zen Mafia. Cali also founded the Hope Gallery in Echo Park (which he ran from 2008-2010) and is now focused on his more recent career as video director (including for King Tuff, Antwon, Hoax, Iceage, Omar Souleyman, Lust for Youth, among others), and finally, his personal work as a fine artist, exhibiting around the world and creating record art for the likes of John Wies, the Repos and Faith No More.

“We became friends after first meeting in 2004,” says Bryan Rae Turcotte, the former office manager of Slash Records, owner of Kill Your Idols publishing company, and owner of Beta Patrol, a music licensing and production company where Cali worked up until recently. “Cali and I started doing projects together soon after that music, art shows, making stuff—stuff we enjoyed doing for love more than money or notoriety.

“It’s so rare these days for any artist to have the ability to focus 100 percent of their energy on their own art and creative projects, but he was able to break away from the day-to-day grind of working for others in early 2014, and focus on his own work exclusively. He’s earned that for himself, in my opinion, by being so dedicated to his own vision without wavering or compromising. His work embodies real ‘heart’ and that’s so amazing to me.”

Cali’s entrée into the art world—with recent solo shows in Hong Kong, Berlin and Copenhagen—has shown that his improvisational, DIY operating style can also be applied to art in a more traditional sense: photographs, screen prints—sure, but also embroidered American flags and reproductions of LA swap meet gang clothing from the Eighties, all using a gang-inspired font that is unmistakably Southern Californian.

“I am a product of this city [Los Angeles],” he told me the first time we met to talk about his work. “I am a part of it, and it's a part of me.”

His screen prints—many of which are wall poster sized—are anchored by one full or several colored images that set the tone for the piece, followed by a phrase that denotes something ironic or attention-grabbing, like an Internet meme meant to shock: A bouquet of flowers in a vase displayed on a perfectly white countertop has the word “ADULTERY” embellished across the middle of the picture, in fat-block letters, stylized by a sans serif font. In another print, the words “Quick,” “Pain” and “Relief” are juxtaposed with two images of handguns. A print with a car on fire is emblazoned with the words “INTIMATE HISTORY.” A full wall of block images of nuclear explosion, repeated like a Wheel of Fortune game board, reads “I BELIEVE IN MAGIC.”

You can almost imagine Vanna White turning the letters to spell out the phrase.

Each one of these pieces speaks to our modern tabloid culture; a world of fake reality TV, celebrity hero worship, infidelity, betrayal, not to mention the death and carnage that have become commonplace in our gun-obsessed culture.

Cali is very much a product of the pop culture he grew up with and is still surrounded by. But it was a seminal stint, as one of the youngest people in the room, at Jabberjaw, the premiere outsider punk venue of the late Eighties and mid-Nineties, which first helped set him on a course he’s followed for the last 20 years.

Earlier this year, he told the web site Highsnobiety that “any vulgarity that seeps through [into my work] is because life is vulgar. My life is vulgar. Being a human is unavoidably vulgar, and my pics are not glammed up at all. I don’t really think about any juxtaposition, I just want to see it all in its natural state.”

Cali’s creative impulse, he says, “Grew out of going to punk and hardcore shows.” He has said this before, in several interviews, but it is an experience that applies to a whole generation of young punks from the 1990s, myself included. “That’s probably where I learned the most,” he tells me. “It was these core-beliefs that shaped my personal and creative life, and helped me learn to deal with the world.” In other words, punk rock is more than just a music scene or subculture. It is a system of beliefs.

Cali is also a cycle enthusiast, which can be rare in a town like Los Angeles. It comes from years of riding a skateboard around town when he was young. “You take in Los Angeles completely differently when you’re riding a board or a bike versus driving a car,” he says.

It’s not hard to see a pattern of progression in Cali’s work. His friends—and past and present collaborators—have all witnessed a swatch of it.

“Cali has his own language,” says Darren Romanelli, an art collector, old friend of Cali’s and owner of Street Virus, a digital marketing agency on the Miracle Mile. “I’ve followed Cali’s progression from behind-the-scenes player to artist-out-in-front himself.” Admittedly, Romanelli says, “The artists I tend to follow and collect live in their own world. Cali is definitely one of those people. We first bonded over trading work. I would give him some of my clothing wares (in this case, I made him a jacket); and in exchange, he shot portraits of my family. Cali nerds out, like I do, over fashion.”

“Honestly,” Romanelli goes on, “who’s more LA than Cali? The t-shirts, the zines, the photos, the screen prints, the record label—he’s always been trying to capture the spirit of this town, and having grown up here, I can appreciate that.”

“One day I get a call from Cali,” says David Kramer, the founder of Family Bookstore, and current Creative Director for creative agency Imprint Projects. “and he says, ‘Hey, there’s this space that’s opening up off Echo Park Avenue, maybe we should get it and set up this gallery, and just see what happens.’ It was month to month, at least that is how it felt. ‘Let’s see how long we can keep it open.’

The result was duo co-founding the Hope Gallery. “That was the plan,” explains Kramer, “and it worked for almost two years.”

“It was a really tiny space, but we put together some great shows in the first few months,” says Kramer. “We did four shows, and sold almost everything. We were quite comfortable, and then the financial crisis hit, and we thought to ourselves: Is this the right time to be doing this? We didn’t lose any money, and it was time to pack it in.”

“With everything Cali does,” Kramer says about Cali’s creative process, “there’s almost a religious sensibility to what he’s doing. He really makes his life almost religiously about his art, and I think it’s why a lot of people treat him in this guru-like fashion—it’s either that or AA dogma [laughs]. Anyhow, he’s the kind of guy where everything he does is by intention and informed by a daily practice—that’s probably the best way to put it.”

“I remember Cali more as a photographer,” says art director and graphic designer Brian Roettinger, a long-time friend and frequent collaborator, about first meeting Cali, more than 20 years ago. “But he was never interested in it as a career—he just kind of went with it, and obsessively documented his life. But it’s not just that, it’s like starting a hardcore band—you don’t think you’re going to sign a record label deal and make a million dollars. You just do it, because that’s what you do.

“Cali does what he does out of a general curiosity. He purposely makes things to make people slightly uncomfortable. Something is off—off in that it’s offensive, or off in that it’s not visually pleasing. But that’s the point.”

“As to the point where Cali became an artist,” Roettinger says, “I remember his 30th birthday party. When he was 29 he took a Polaroid of someone every day and then at this 30th birthday party, he had an exhibition with 365 Polaroid photos of people he had encountered that previous year. I made the poster for it, actually. That was the first time I remember him exhibiting something one could consider his own work.”

“To me, Cali is relevant now more than ever,” says Romanelli, “because he has a consistent dialogue with the public, his friends, his family—and you can’t say that about most people no matter what discipline they practice.”

So what is Cali Thornhill DeWitt working on next?

I sent him this one last question. He replied, matter-of-factly, via email later that night; “Focus/Efficiency/Navigation.”